This legislation, signed into law by President Bill Clinton in November 1999, repealed large parts of the Glass-Steagall Act, which had separated commercial and investment banking since 1933. This led to the creation of financial holding companies, over which the Fed was granted new supervisory powers.

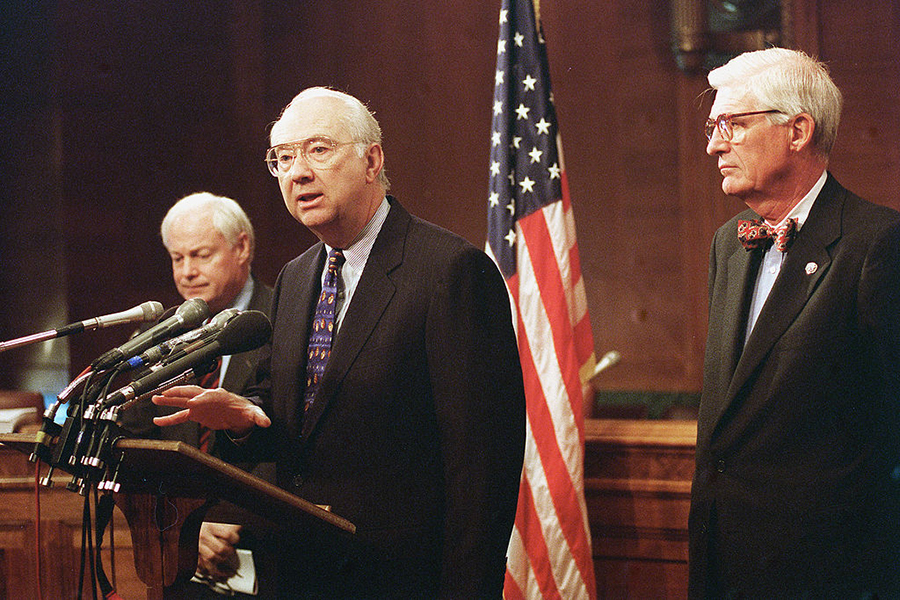

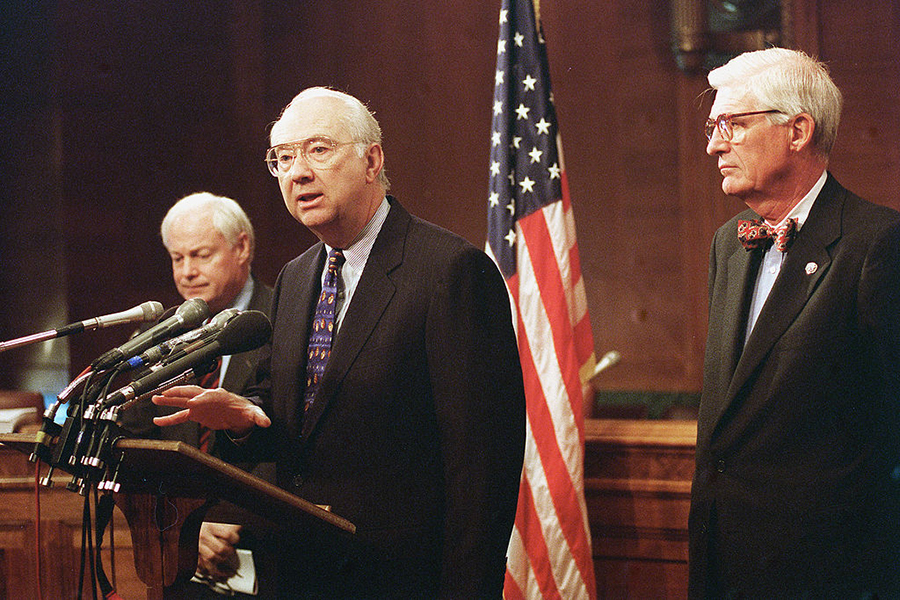

Jim Leach, R-Iowa, Phil Gramm, R-Texas, and Thomas J. Bliley Jr., R-Va., during a press conference on their compromise bill. (Photo: Douglas Graham/CQ-Roll Call Group/Getty Images)

by Joe Mahon, Federal Reserve Bank of MinneapolisBy the late 1990s, consolidation in the banking industry had been an ongoing trend for twenty years. The number of commercial banks in the United States had fallen from more than 14,000 in 1984 to fewer than 9,000 in 1999, while the average size of those banks had grown. This was part of a broader trend of consolidation in financial services industries.

Moreover, financial services that had been separate for the latter half of the twentieth century—commercial banking, investment banking, and insurance—had become more integrated. Beginning in the late 1980s, some commercial banking organizations had started moving into underwriting securities (stocks and corporate bonds) and a few had also begun selling insurance. By 1999, financial integration was well underway, and Congress decided to act. In November, it passed and President Clinton signed the Financial Services Modernization Act (commonly called Gramm-Leach-Bliley, in acknowledgment of its primary sponsors in Congress), rewriting the financial regulation rulebook and giving the Fed new supervisory powers.

The Banking Act of 1933 (Glass-Steagall) had set up a wall of separation between certain sectors of the financial services industry. These restrictions were a response to the perception that commercial and investment banking had become too intertwined leading up to the 1929 stock market crash—that banks had taken undue risk with depositors’ savings in the financial markets or were promoting the securities they underwrote to their customers, leading to conflicts of interest.

However, Glass-Steagall contained language that made some financial integration possible. Most notable was Section 20 of the law, which separated commercial and investment banking. The law prohibited bank affiliation with firms that were “engaged principally” in underwriting and dealing securities. This made it possible for bank holding companies to create subsidiaries or acquire firms involved in some underwriting or dealing, as long as most of their activities were otherwise permissible. The first of these Section 20 subsidiaries was approved by the Fed in 1987, and by 2000 there were fifty-one nationwide.

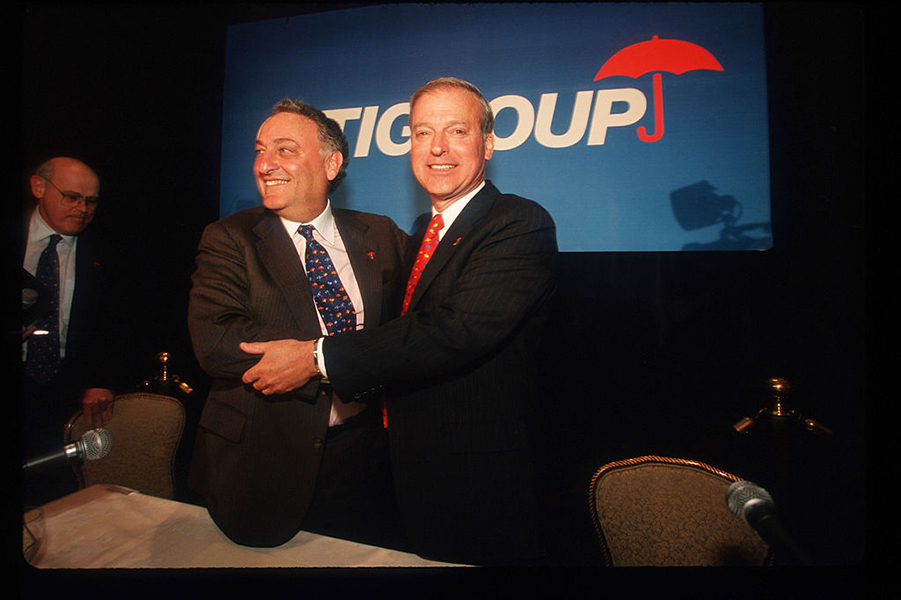

The primary routes for banks to sell insurance were under state laws for state-chartered banks, but national banks were allowed to provide credit-related insurance and operate insurance agencies in small towns where they had bank offices. These laws limited bank insurance activities, but in 1998 Citicorp, a large bank holding company, announced plans to merge with Travelers Insurance, forming Citigroup. This merger was not yet permissible under existing regulations; it was made in anticipation of a change in the law then under discussion in Congress.

Citicorp's CEO John Reed and Travelers Group's CEO Sanford Weill shake hands at a press conference April 6, 1998, in New York City. Reed and Weill announced the merger of their two companies, which would form a new company called Citigroup. (Photo: Porter Gifford/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act addressed these changes in the financial sector. It was intended to promote the benefits of financial integration for consumers and investors while safeguarding the soundness of the banking and financial systems.

The primary change the law ushered in was the creation of a new kind of financial institution: the financial holding company (FHC). A FHC was essentially an extension of the concept of a bank holding company—an umbrella organization that could own subsidiaries involved in different financial activities. This was something of a compromise, as security and insurance underwriting and sales by depository institutions would still be restricted, but banks could be part of a larger corporation that was involved in those activities.

While allowing this kind of affiliation repealed portions of the Glass-Steagall and Bank Holding Company Acts, it created new regulations for FHCs. The law placed cross-marketing restrictions to prevent a bank and a nonbank subsidiary of a FHC from marketing the products or services of the other entity. These restrictions were intended to prevent banks from promoting securities underwritten by other subsidiaries to their customers. In addition, restrictions remained on financial transactions between banks and nonbank subsidiaries.

The law also placed size limitations on banks’ financial subsidiaries. At the time the law went into effect, the total assets of the financial subsidiaries of a national bank were limited to the lesser of $50 billion or 45 percent of its total assets. In order to give these rules teeth, it was necessary to appoint a regulator that would have the power to enforce them. That responsibility fell primarily upon the Federal Reserve.

To form a FHC, a company must file a written declaration with the Federal Reserve Board that it elects to be a FHC, and must also certify that it meets the requirements. The certification requirements were intended to hold FHCs to a higher standard. The subsidiary depository institutions must be well capitalized and well managed in accordance with existing bank regulations, and they must have at least satisfactory ratings under the Community Reinvestment Act. If any of the subsidiaries cease to be well managed or capitalized, the FHC would face corrective supervisory action and be prohibited from undertaking new financial activities until the problems were addressed. FHCs have 180 days to correct their shortcomings, or they could be forced by the Fed to divest their depository subsidiaries or stop engaging in other financial activities. When commencing an authorized financial activity, a FHC must notify the Federal Reserve Board within thirty days after starting the activity.

The Fed’s supervision of FHCs is based on the concept of functional regulation. The Fed supervises the consolidated organization, while primarily relying on the reports and supervision of the appropriate state and federal authorities for the FHC subsidiaries. For example, the Securities and Exchange Commission would regulate the registered securities brokers, dealers, and investment advisers; state insurance commissioners would oversee licensed insurance companies; and the appropriate state and federal banking agencies would supervise banks and thrifts. The law thus kept in place the existing regulators for financial subsidiaries of FHCs, but gave the Fed the role of “umbrella supervisor.”

This role was seen as necessary because these large and complex financial institutions had risk spread across their subsidiaries, but managed it as a consolidated entity; someone had to oversee the operation of all the moving parts. Furthermore, the goal of the law was to protect banks and their customers from risks taken on at financial subsidiaries, while ensuring that the protections for banks (e.g., deposit insurance) were not extended to nonbank affiliates, thereby creating perverse incentives for risk management.

The financial crisis of 2007-08 has caused many to call into question how effectively the law carried out its goals. It is probably too early to answer definitively, but a few questions can be posed:

There is an active debate over these and other questions, and some have called for substantial changes to Gramm-Leach-Bliley. But it remains for future historians to answer these questions definitively.

Furlong, Fred. “The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act and Financial Integration.” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter 2000-10, March 31, 2000.

Yeager, Timothy J., Fred C. Yeager, and Ellen Harshman. "The Financial Services Modernization Act: Evolution or Revolution." Journal of Economics and Business 59, no. 4 (July-August 2007): 313- 39.

Written as of November 22, 2013. See disclaimer.